There is a building on the corner of First Street and Alameda in the Little Tokyo section of downtown Los Angeles. The building is completely made of bricks, something of a rarity in Los Angeles due to the presence of the many fault lines that run beneath the city.

There is a building on the corner of First Street and Alameda in the Little Tokyo section of downtown Los Angeles. The building is completely made of bricks, something of a rarity in Los Angeles due to the presence of the many fault lines that run beneath the city.

The bricks are old, over a hundred years, and the earthquake reinforcements shaped like stars and bolted to the walls are beginning to show their age. The building is freshly painted but beneath the new paint are layer upon layer of memories from another Los Angeles; a Los Angeles that stretched and grew after World War II in leaps and bounds.

Sometimes the growing pains were difficult, unapologetic and burned through with the racist legacy of our national xenophobia. But in the end, the willingness to overcome disgraceful and bigoted public policy often led to some multi-cultural results that became a part of the best Los Angeles, a city I once knew.

Before there was a building there, the corner of First & Alameda was vineyards. It seems that in the 1800’s downtown Los Angeles was a great place to grow wine grapes. It was also becoming a mini-metropolis and in 1901 both the Los Angeles Railway and the Pacific Electric Railway (Red Cars) were operational. By the 1920’s, the Red Cars were the largest electric railway system in the world, connecting San Bernardino, Riverside, Orange and Los Angeles counties.

It seems odd to imagine, all these years later, as Los Angeles once again struggles to join the modern era of mass transit. The destruction of the Red Cars in Los Angeles is well documented and worth reading about. (Or you could watch “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”) But perhaps that is also a quintessential parable of Los Angeles, a city that constantly destroys itself in order to rebuild itself again.

It seems odd to imagine, all these years later, as Los Angeles once again struggles to join the modern era of mass transit. The destruction of the Red Cars in Los Angeles is well documented and worth reading about. (Or you could watch “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”) But perhaps that is also a quintessential parable of Los Angeles, a city that constantly destroys itself in order to rebuild itself again.

In the late 1800’s the land was subdivided and in just a few years the corner of First and Alameda went from vineyards to brewery. Some time later the area quickly became the bustling and prosperous center of the Japanese-American community in Los Angeles.

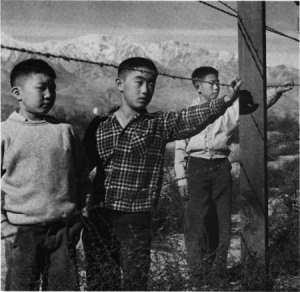

And then came Pearl Harbor and on February 19, 1942 President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that forced the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps in remote locations including many citizens whose parents and grandparents were born in this country.

And then came Pearl Harbor and on February 19, 1942 President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that forced the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps in remote locations including many citizens whose parents and grandparents were born in this country.

In Japanese the numbers 1, 2, 3 are pronounced ichi, ni, san. Hence the perfectly descriptive terms Isei, Nisei and Sansei to connote first, second or third generation Americans, all of whom were taken to camps.

The area was soon populated by African-Americans and for a while was even called Bronzeville. Then the war was over and those able to return and rebuild, did so. Some started new businesses like Ito and Minoru Matoba. In 1946 they opened a small neighborhood diner serving noodles and Japanese fare alongside hamburgers and fries and gave it the rather bold name “Atomic Café.” I once asked Mr. Matoba why he chose the name “Atomic” considering it was so soon after WW II and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He replied, “People will always remember the atomic bomb. Maybe they will always remember the Atomic Café.” In 1961 the diner relocated to the corner of First Street and Alameda.

The area was soon populated by African-Americans and for a while was even called Bronzeville. Then the war was over and those able to return and rebuild, did so. Some started new businesses like Ito and Minoru Matoba. In 1946 they opened a small neighborhood diner serving noodles and Japanese fare alongside hamburgers and fries and gave it the rather bold name “Atomic Café.” I once asked Mr. Matoba why he chose the name “Atomic” considering it was so soon after WW II and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He replied, “People will always remember the atomic bomb. Maybe they will always remember the Atomic Café.” In 1961 the diner relocated to the corner of First Street and Alameda.

By the mid-seventies the center of the city had evolved yet again and years of suburban flight had caused the area around First and Alameda to become a no man’s land. Empty warehouses surrounded the café and once thriving businesses either relocated or closed their doors forever. But the Atomic lingered on, with Mr. and Mrs. Matoba in the kitchen or waiting on customers, just like they had for the previous thirty years.

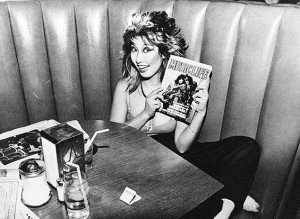

When punk music hit the city in 1977, the Atomic Café was reborn. Nancy Sekizawa, daughter of the owners and herself a former singer with the band Hiroshima, decided to plaster the walls and ceiling of the café with posters and fliers for punk bands. The jukebox, already a mix of standards, classic rock and roll and Japanese songs also began to reflect this shift. In short order the jukebox at the Atomic was perfectly suited to its clientele and provided the soundtrack for a cultural mashup the likes of which we may never see again.

When punk music hit the city in 1977, the Atomic Café was reborn. Nancy Sekizawa, daughter of the owners and herself a former singer with the band Hiroshima, decided to plaster the walls and ceiling of the café with posters and fliers for punk bands. The jukebox, already a mix of standards, classic rock and roll and Japanese songs also began to reflect this shift. In short order the jukebox at the Atomic was perfectly suited to its clientele and provided the soundtrack for a cultural mashup the likes of which we may never see again.

Nancy changed the records often but she always managed to maintain the integrity and unexpected asymetry that made the Atomic jukebox so unique. It was not uncommon to hear, all in one stretch, White Riot, Be-Bop-A-Lula, Money-That’s What I Want, Sukiyaki and My Way by both Frank Sinatra and Sid Vicious.

In all the years I was a customer at the Atomic Café I never once witnessed any of the reverse discrimination practiced by some of their neighbors with their “No Gaijin” policy so prevalent in Tokyo, Japan.

In addition to the punks and music fans there were many other customers at the Atomic as well. There were the “regulars,” people from the neighborhood who don’t move because a neighborhood changes, artists from the surrounding lofts and a few Japanese “shady types.” Together, they gave the place an incomparable authenticity. You can’t design places like this. There is no “market research” to target this audience. It was a real city hangout, a neighborhood joint, an urban mix of what once was and what it was becoming.

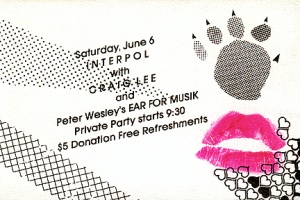

Two doors from the Atomic Café and contained within the same building another business that catered to the music scene emerged. The Brave Dog, a music venue/underground club would operate on weekends at 418 East First Street. And in a triangle shaped wedge of the building attached to the back of the Atomic there were a few more underground concerts and an early performance by artist John Duncan.

Two doors from the Atomic Café and contained within the same building another business that catered to the music scene emerged. The Brave Dog, a music venue/underground club would operate on weekends at 418 East First Street. And in a triangle shaped wedge of the building attached to the back of the Atomic there were a few more underground concerts and an early performance by artist John Duncan.

Politically, I prefer that many small grants be given to worthy cultural and civic institutions instead of large bulk handouts to Wall Street bankers as a means to spur the economy. Federal programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) did wonders during the Depression and created some lasting and important art that we still appreciate today. I doubt the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (Wall St. Bailout) will enhance my cultural life in any significant way.

In the late seventies and early eighties there was another lesser-known federal program called the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) that gave small amounts to galleries and museums in order to augment their staff with part time labor. As a youngster in college I was one such employee at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA). The time I spent working at LAICA downtown was one of the most fertile and creative I have known. At that age it was a profound experience to live and work interacting with artists in an art space that published a journal as well.

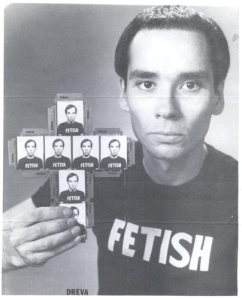

My colleagues at LAICA were a bit older and very busy with their work. One of them however always took time to include me in the proceedings. His name was Jerry Dreva. He was always generous and thoughtful towards me. Whenever something interesting was about to happen in town or at LAICA, he would be sure to let me know. I remember the day he called to say I should come down and meet Alfredo Nuñez, a visiting artist from Mexico, of the performance art group “No Grupo.” This meeting was a catalyst for so much of the artwork that I did later and I was so glad for that introduction. That was Dreva.

My colleagues at LAICA were a bit older and very busy with their work. One of them however always took time to include me in the proceedings. His name was Jerry Dreva. He was always generous and thoughtful towards me. Whenever something interesting was about to happen in town or at LAICA, he would be sure to let me know. I remember the day he called to say I should come down and meet Alfredo Nuñez, a visiting artist from Mexico, of the performance art group “No Grupo.” This meeting was a catalyst for so much of the artwork that I did later and I was so glad for that introduction. That was Dreva.

LAICA was at 815 Traction Ave and just up the street on Hewitt, Mark Kreisel was painting the wooden floors of the soon-to-be-opened American Hotel and Al’s Bar.

Soon after, another downtown mainstay would open. Gorky’s, a brightly lit, self-serve, cafeteria-style, restaurant that catered to the art community. It sat a few blocks south near 8th Street. New restaurants and bars were beginning to pop up while old fashioned ones like Koma on First Street and Yee Mee Loo in Chinatown provided a window onto another world, a world born shortly after WW II. The city was changing.

Like two panes of glass overlaid on one another, slowly creeping their separate ways, one to the left and toward the past and the other to the right and a bright new future, postwar-downtown Los Angeles was in the middle, occupying the slowly decreasing overlap that would soon disappear completely.

I remember playing pool at a coffee shop near Al’s Bar. Beer was $1.50 and pool was fifty cents. I signed my name on the wall and after a short time I found myself playing against a six-foot-tall woman with heavy makeup and a deep gravelly voice. She had big hands and played great pool but she might have trouble with an Olympic gender screening. No matter, she was a good pool player. She had her own cue and at the butt end was a brass ball about the size of a small grapefruit. When she broke it sounded like a cannonball. Needless to say, she made short work of me.

I remember playing pool at a coffee shop near Al’s Bar. Beer was $1.50 and pool was fifty cents. I signed my name on the wall and after a short time I found myself playing against a six-foot-tall woman with heavy makeup and a deep gravelly voice. She had big hands and played great pool but she might have trouble with an Olympic gender screening. No matter, she was a good pool player. She had her own cue and at the butt end was a brass ball about the size of a small grapefruit. When she broke it sounded like a cannonball. Needless to say, she made short work of me.

The Atomic Café was walking distance from LAICA and the American Hotel and the aforementioned café with pool table. The sly and ironic artist Teddy Sandoval had a studio on Banning Street just a two-minute walk away. His studio was one of several gathering places for the underground glitterati of the era.

There were a few galleries downtown as well, Kirk de Gooyer and Cirrus, and Lowinsky and Arai, (a photo gallery from San Francisco). I remember a group show that featured “Moonrise Over Hernandez, New Mexico” by Ansel Adams. The show also included works by Edward Weston and a very young Robert Mapplethorpe among others. I still recall how thrilled I was to be able to see original, new and vintage prints up close and not have to travel across town to a museum or Westside gallery.

Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) was nearby just over on Broadway. LACE was the scene of the infamous Dreva/Gronk show in 1978 where “Art” met “Punk.” The Bags, featuring Alice Bag (née Armendariz) played and the overly enthusiastic crowd had to be dispersed by the ever-vigilant LAPD.

It seems like yesterday but these events I describe were more than thirty years ago. Now I find myself once again, reminiscing about places that no longer exist, like the cavernous old style pool hall in the basement of the Santa Fe building with turn-of-the-century Brunswick tables and yellowing black and white snapshots, not posters, of Willie Moscone and Minnesota Fats, thumb-tacked to the grimy smoke stained walls, shooting pool at these same tables.

That pool hall, the Main Street Gym, Johnny’s Shrimp Boat, Natick’s Hobby Shop and old gay bars like Harold’s and the Waldorf, are all gone. The Atomic Café served its last Go-Go Chicken in 1989.

Imagine all of these places within walking distance, in a town where no one walks. It couldn’t last, and it didn’t. Soon, flophouses gave way to condos and the new face of downtown began to emerge, seemingly unrelated to the old one.

In 1977 and for a few short years, downtown Los Angeles was a wonderland. It was that perfect combination of old and new, when small entrepreneurs and artists (now sometimes referred to as “creative capital” a term that makes my skin crawl) work together to serve a community of people not shareholders.

On the outskirts of the civic center of Los Angeles, and much closer to the ragged edge of the city, the burgeoning art scene co-existed with the punks in this nether world of bohemians, tramps, junkies, mobsters and world class artists.

On the outskirts of the civic center of Los Angeles, and much closer to the ragged edge of the city, the burgeoning art scene co-existed with the punks in this nether world of bohemians, tramps, junkies, mobsters and world class artists.

If it could all be boiled down to one place, one nexus, one geographical location that served as ground zero where all these disparate groups met, where there was no animosity, no cultural arrogance, and certainly no exclusionary practices it was surely the iconic and legendary Atomic Café.

For close to twenty years the building also housed a restaurant called Señor Fish. It too served its final meal last Saturday. Next year the building will be demolished to construct a new subway station.

The hundred year old bricks bear witness to the evolution of a city. A city and a café where electric railway cars once rolled past and punks, artists and Yakuza once sat side by side eating noodles and listening to the Clash, Gene Vincent and Frank Sinatra. The Little Tokyo Service Center would like to preserve a part of the building and the legacy of the Atomic Cafe before it is demolished. As a third generation American of Mexican descent or “Sansei” I think it is a worthy endeavor.

beautiful post. I went to Gorky’s in the very early 80’s, and its great to get a piece of its earlier history — a history I never witnessed. thanks very much.

A very, very wonderful article, Sean!

Hello Sean,

It has been many years since our last contact. Thank you so much for plugging in the Atomic Café. I was very pleased to see that you wrote the story. I still remember you back in the day being so active in the community. You were always very enthusiastic and kind. The Atomic Cafe/Troy event was very successful. Everyone came that you would remember.

I hope to visit NY someday soon and chat with you over coffee. Until then, Zen and I wish you and your family all the best.

a.tomic n.ancy

Sean,

I just had lunch with Nancy (Atomic Nancy) in J-Town and we were looking at the picture of the Atomic Cafe in your article. We think it might be a picture of the first location (first of three locations) opened in 1946, where did you get the picture and do you have any other information about it?

Thanks

Hi Sean and Nancy,

I’ve been loving reading and exploring the history of both the Atomic Cafe and Cafe Troy. I run a local art guide and magazine called Get Down Town. We’re hosting a recurring event series about movements throughout Downtown LA history, cultural, social, political, and would love to do a panel event on women-run and feminist-fueling spaces in Downtown’s history. It would be amazing to have both of you (and/or your wife, Sean) share with the current Downtown community about your businesses and the culture you fueled there. Please email me if you see this – ari@getdowntown.la. Would love to discuss more.

A friend just sent me this great article. I lived at 3rd and San Pedro in downtown from 1977-1983. Our loft was about

3,000′ for about $500 a month. The building had a shoe factory and hammered all day. The next day the dumpsters were

filled with pink feathers and lots of discarded wooden platform patterns. Some events were repetative like the backwards

walker, others happened only once like the rooftop full of colorful straw hats drying in the sun. I loved seeing the lights on at night and could almost name who was up making art by their location. Something wonderful was always going on – from the three guys perched on a discarded sofa singing “Duke of Earl”, the trucks rolling by with the 4′ wide paper rolls destined for the LA Times, to the late night tap dancer on third street. It was a magical time and the Atomic Cafe was part of the neighborhood.

Great read. I have been living in Little Tokyo for four years, but I didn’t know much about Atomic Cafe until shortly before it closed as Senor Fish. I used to drive by it in the ’80s when it was Atomic Cafe; it was always an intriguing place to me, but I sadly never got around to actually going inside. Fort what it’s worth, I got a portion of one of those bricks from the demolition site right after it came down.

Reblogged this on Mugwort and commented:

Wow. This bought back memories of Gracie and Yvonne when we were 17. Gorky’s.

Thanks for the memories, Sean. Wish I’d gone to Atomic Cafe more. Say give my best to Bibbe!